“Writing and City Life” Class 11 History Theme 1″Early Societies”: The notes are detailed and comprehensive to help students grasp the whole chapter “Writing and City Life” of Class 11 history textbook. Notes are given under proper headings and subheadings to make them sustained and easily understandable in the context of the chapter “Writing and City Life”. So, enjoy the free learning resources here 👍😊

Video of Notes Series on ‘Writing and City Life’

Theme 1: Early Societies

The following notes discuss emergence of early societies, the development of settlements and agriculture, and the significant changes that led to the growth of cities and trade. The transition from a nomadic lifestyle to settled agriculture had profound effects on human civilization.

- Early Societies:

- Beginnings of human existence trace back millions of years ago.

- Humans first emerged in Africa.

- Archaeologists study early history through remains of bones and stone tools.

- Attempts to reconstruct early people’s lives, including their shelters, food arrangements, and how they expressed themselves.

- Important developments: use of fire and language.

- Early Cities in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq):

- Cities developed around temples and were centres of long-distance trade.

- Archaeological evidence and written materials help reconstruct the lives of different people in these cities.

- Pastoral people played significant roles in some towns.

- Question: Would the many city activities have been possible without writing?

- Shift from Nomadic Life to Settlements and Agriculture:

- The shift began around 10,000 years ago.

- Before agriculture, people gathered plant produce for food.

- Gradually learned to grow plants, cultivate crops like wheat, barley, peas, millet, and rice.

- Domesticated animals (sheep, goat, cattle, pig, and donkey) and used plant and animal fibers for cloth.

- Domesticated animals were later harnessed to ploughs and carts.

- Impact of Settlements and Agriculture:

- Settled life became more common due to the need to tend to crops.

- People built more permanent structures for living.

- Earthen pots used to store and process food from cultivated grains.

- Stone tools evolved with smoothening and polishing techniques.

- Metal ores like copper and tin were tapped for jewellery and tools.

- Increasing trade led to the growth of villages, towns, and small states.

- Far-Reaching Revolutionary Consequences:

- The shift to agriculture and settled life transformed people’s lives significantly.

- Trade, growth of cities, and movement of people accelerated change.

- Some scholars describe this period as a revolution in human society.

I. Mesopotamian City and Early Languages

These notes highlight the connection between city life and writing in Mesopotamia, as well as the linguistic developments and cultural exchanges that took place in the region throughout history.

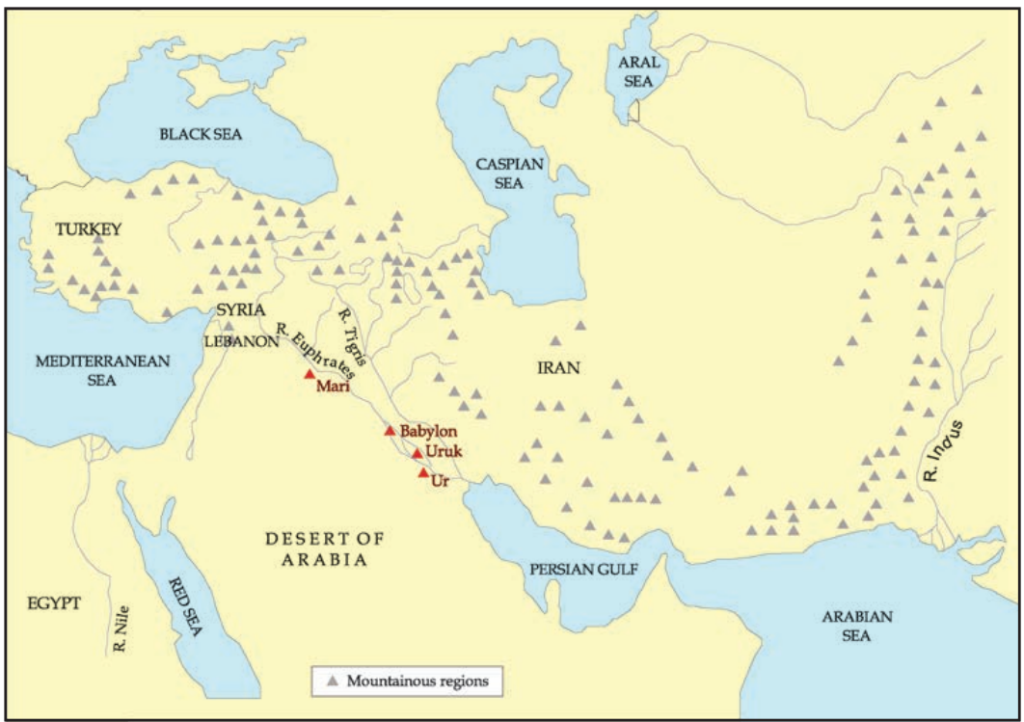

- Mesopotamia, located between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers (now part of Iraq), is the birthplace of city life and civilization.

- Mesopotamian civilization is renowned for its prosperity, urbanization, extensive literature, and advancements in mathematics and astronomy.

- The influence of Mesopotamia’s writing system and literature spread across the eastern Mediterranean, northern Syria, and Turkey after 2000 BCE.

- This led to the adoption of Mesopotamian language and script by kingdoms in the region, enabling communication with one another and even the Pharaoh of Egypt.

- The early recorded history of the region referred to the urbanized south as Sumer and Akkad.

- After Babylon rose as an important city, the term Babylonia was used to denote the southern region.

- The establishment of the Assyrian kingdom in the north around 1100 BCE led to the region being known as Assyria.

- The earliest known language in Mesopotamia was Sumerian, which eventually gave way to Akkadian around 2400 BCE with the arrival of Akkadian speakers.

- Akkadian thrived until the time of Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE), with some regional variations occurring over time.

- Around 1400 BCE, the Aramaic language began to gain influence in the region, similar to Hebrew, and became widely spoken after 1000 BCE.

- Aramaic continues to be spoken in parts of Iraq to this day.

Archaeology and European Interest in Mesopotamia:

These notes highlight the development of archaeology in Mesopotamia, the initial interest in validating Biblical accounts, and the subsequent shift towards a more nuanced understanding of ancient Mesopotamian civilization and its significance.

- Archaeological exploration in Mesopotamia began in the 1840s, with long-term excavations conducted at sites like Uruk and Mari.

- These excavations provided valuable sources for studying Mesopotamian civilization, including buildings, statues, ornaments, graves, tools, seals, and thousands of written documents.

- Mesopotamia held significance for Europeans due to its references in the Old Testament, particularly the Book of Genesis, which mentioned Sumer as a land of brick-built cities.

- European travellers and scholars considered Mesopotamia as an ancestral land, and there was an initial effort to validate the literal truth of the Old Testament through archaeological work.

- From the mid-nineteenth century, there was a growing enthusiasm for exploring the ancient past of Mesopotamia.

- In 1873, a British newspaper sponsored an expedition by the British Museum to search for a tablet recounting the story of the Flood mentioned in the Bible.

- By the 1960s, it became widely understood that the stories in the Old Testament were not necessarily literal accounts but likely represented symbolic expressions of important historical changes.

- Archaeological techniques became more sophisticated and refined, with a shift in focus toward reconstructing the lives of ordinary people and exploring different research questions.

- The pursuit of establishing the literal truth of Biblical narratives took a backseat, and subsequent studies in Mesopotamian archaeology built upon these later approaches.

Biblical Flood Story and its Mesopotamian Parallel:

These notes highlight the parallels between the Biblical flood story and the Mesopotamian flood narrative, emphasizing the similarities in the choice of a protagonist, the construction of an ark, and the preservation of animals during the cataclysmic event.

- According to the Bible, the Flood was intended to annihilate all life on Earth, but God chose Noah to preserve life and instructed him to build a massive boat called an ark.

- Noah gathered pairs of all known species of animals and birds onto the ark, ensuring their survival during the Flood.

- Interestingly, a similar story exists in the Mesopotamian tradition, where the central character is referred to as Ziusudra or Utnapishtim.

- In the Mesopotamian version of the flood narrative, Ziusudra/Utnapishtim is also chosen to build an ark to escape the catastrophic flood.

- He likewise gathers pairs of animals and birds to save them from the deluge.

- The parallel between the Biblical and Mesopotamian flood stories suggests a shared cultural motif or a potential cultural exchange between these civilizations.

- The similarities between these narratives raise questions about the influence and interconnections between ancient cultural traditions.

II. Mesopotamia and its Geography

These notes highlight the diverse environments in Iraq, the significance of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers for agriculture, and the abundance of resources such as livestock, fish, and date-palms. The connection between rural prosperity and the growth of cities will be further explored.

Iraq’s Diverse Environments and Agriculture in Mesopotamia:

- Iraq exhibits a variety of environments, with green, undulating plains in the northeast gradually transitioning into tree-covered mountain ranges with streams and wildflowers. Sufficient rainfall in this region allows for agriculture, which began around 7000-6000 BCE.

- In the north, there is an upland known as a steppe, where animal herding is a more viable livelihood than agriculture. After winter rains, sheep and goats graze on the grasses and low shrubs that grow in this area.

- To the east, the tributaries of the Tigris River serve as communication routes into the mountains of Iran.

- The southern part of Iraq is characterized by desert, where the first cities and writing emerged.

- The desert region could support cities due to the presence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. These rivers, originating from the northern mountains, carry fertile silt and deposit it when flooding or when water is released onto the fields.

- The floodwaters from the rivers flow into small channels that functioned as irrigation canals in the past, allowing water to be directed to wheat, barley, peas, or lentil fields as needed.

- Despite the limited rainfall, the agriculture of southern Mesopotamia was remarkably productive, thanks to the efficient irrigation systems.

- In addition to agriculture, the Mesopotamian region supported abundant livestock, such as sheep and goats, which grazed on the steppe, northeastern plains, and mountain slopes. These animals provided meat, milk, and wool.

- The rivers also provided a source of fish, while date-palm trees bore fruit in the summer.

- While rural prosperity played a role in the growth of cities, other factors will be discussed later, highlighting that city life was influenced by more than just agricultural success.

The Significance of Urbanism

These notes emphasize that urban economies extend beyond food production and involve trade, manufacturing, and services. Specialization, division of labour, social organization, and the need for written records play significant roles in facilitating the functioning and interdependence of urban societies.

Urban Economies and Social Organization:

- Cities and towns are more than just densely populated areas. They emerge as advantages when economies develop beyond food production, encompassing trade, manufacturing, and services.

- Urban economies consist of various sectors, including food production, trade, manufacturing, and services. City dwellers become interdependent, relying on the products and services provided by others in the city or surrounding villages.

- Continuous interaction occurs among people with different specializations and skills. For example, a stone seal carver may require bronze tools and coloured stones, which they do not possess or know where to acquire. Specialization in a particular craft or trade becomes a characteristic of urban life.

- The division of labour is a key aspect of urban life, as different individuals specialize in specific tasks or trades.

- Urban economies necessitate organized trade and storage. Various resources such as fuel, metals, stones, and wood are sourced from different places to support city manufacturers.

- Social organization is essential for coordinating diverse activities. Trade and storage systems must be established to facilitate the delivery, storage, and distribution of goods, including grain and other food items from villages to cities.

- Coordinated efforts are required to ensure the availability of essential items for different professions. For example, seal cutters not only need stones but also bronze tools and pots. This coordination often involves hierarchical relationships, where some individuals give commands that others obey.

- Written records are often crucial in urban economies to keep track of transactions, inventories, and other important information.

III. Movement of Goods into Cities

These notes highlight the importance of trade in acquiring essential resources for Mesopotamia, the significance of efficient transport, and the role of waterways in facilitating trade and economic development in the region.

Trade, Transport, and Resources in Mesopotamia

- While Mesopotamia was rich in food resources, it had limited mineral resources. The southern parts of Mesopotamia lacked stones for tools, seals, and jewellery, and the available wood from date-palms and poplar was unsuitable for carts, wheels, and boats. Additionally, there was a scarcity of metal for tools, vessels, and ornaments.

- It is believed that the ancient Mesopotamians engaged in trade to acquire necessary resources such as wood, copper, tin, silver, gold, shells, and various stones. They likely traded their abundant textiles and agricultural produce with regions like Turkey, Iran, and across the Gulf, which had mineral resources but less agricultural potential.

- Regular exchanges and trade routes were facilitated by the social organization of the people in southern Mesopotamia, enabling foreign expeditions and the acquisition of desired resources.

- Efficient transportation is crucial for urban development. If transporting grain or charcoal into cities requires too much time or animal feed, the city’s economy will suffer. Water transportation, such as river boats or barges, was the most cost-effective mode of transportation in ancient times.

- The canals and natural channels of Mesopotamia served as routes for goods transport between large and small settlements. These waterways played a significant role in facilitating trade and transportation, and the Euphrates River, in particular, served as a vital “world route” for the city of Mari, as discussed later in the chapter.

Early Cities in Mesopotamia and the Use of Bronze:

- The earliest cities in Mesopotamia emerged during the Bronze Age around 3000 BCE.

- Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, played a crucial role in the development of these cities.

- The use of bronze necessitated the acquisition of copper and tin, often from distant locations.

- Metal tools made from bronze were essential for various tasks such as precise carpentry, drilling beads, carving stone seals, and cutting shell for inlaid furniture.

- Bronze was also used for crafting weapons in Mesopotamia. For example, the tips of spears were made of bronze.

IV. The Development of Writing

These notes highlight the emergence and evolution of writing in Mesopotamia, its association with record-keeping and transactional purposes, and the longevity of cuneiform writing in the region. The transition from pictographic signs to the cuneiform script and the shift from Sumerian to Akkadian demonstrate the development and adaptation of writing systems over time.

Development of Writing & Script in Mesopotamia:

- Writing, as a form of verbal communication, represents spoken sounds through visible signs.

- The emergence of writing can be attributed to the need for record-keeping in city life, where transactions occurred at different times, involved numerous individuals, and encompassed a variety of goods.

- Writing in Mesopotamia began around 3200 BCE, with the earliest tablets containing picture-like signs and numbers.

- These early writings primarily comprised lists of goods, such as oxen (5000 lists), fish, and bread loaves, that were brought into or distributed from the temples of Uruk, a city in southern Mesopotamia.

- Mesopotamians primarily wrote on clay tablets. A scribe would wet clay and shape it into a manageable size that could be comfortably held in one hand.

- Using a reed with a wedge-shaped end (cuneiform), the scribe would press signs onto the moist clay. Once dried, the clay tablets became nearly indestructible.

- Each transaction required a separate written tablet, resulting in hundreds of tablets found at Mesopotamian sites. The abundance of these tablets provides a wealth of information about Mesopotamian society.

- By around 2600 BCE, the writing system transitioned to cuneiform, and the language used was Sumerian.

- Writing served purposes beyond record-keeping, including creating dictionaries, establishing legal validity for land transfers, narrating the deeds of kings, and announcing changes in customary laws.

- After 2400 BCE, the Akkadian language gradually replaced Sumerian as the predominant language in Mesopotamia. Cuneiform writing in Akkadian continued to be used for more than 2,000 years, until the first century CE.

V. The System of Writing

These notes emphasize that cuneiform writing involved representing syllables rather than individual sounds and required scribes to learn a large number of signs. Writing in cuneiform was considered both a skilled craft and a significant intellectual achievement as it visually captured the complex sound system of the Mesopotamian language.

Cuneiform Writing in Mesopotamia:

- Cuneiform writing in Mesopotamia represented syllables rather than individual consonants or vowels.

- Each cuneiform sign represented a syllable, such as “say,” “put,” “la,” or “in,” rather than a single sound.

- Learning cuneiform required scribes to familiarize themselves with hundreds of signs, each representing a specific syllable.

- Scribes had to work quickly to inscribe the signs on wet clay tablets before they dried, adding to the skill and dexterity required for writing in cuneiform.

- Writing in cuneiform was not only a skilled craft but also an impressive intellectual achievement. It allowed for the visual representation of the complex sound system of a particular language.

VI. Literacy

These notes underscore the limited literacy rates in Mesopotamia and the functional aspects of writing, such as letters being read aloud and the connection between written and spoken language. The significance of oral transmission is highlighted in the context of literary compositions, with an emphasis on the importance of teaching and passing down knowledge through generations.

Literacy and the Function of Writing in Mesopotamia:

- Only a small portion of the Mesopotamian population was literate, capable of reading and writing.

- Learning to read and write in cuneiform required extensive knowledge of complex signs, making literacy a rare skill.

- Kings and rulers who possessed literacy often highlighted this ability in their inscriptions to showcase their status and accomplishments.

- In official correspondence, if an official wrote a letter to the king, it would be read aloud to the recipient.

- The content of the letter would typically begin with an address to the king, followed by the message from the servant who carried out assigned tasks.

A letter from an official would have to be read out to the king. So it would begin:

‘To my lord A, speak: … Thus says your servant B: … I have carried out the work assigned to me …’ - Writing in Mesopotamia primarily reflected the spoken language, maintaining a close connection to oral communication.

- Literary compositions, such as mythical poems, were intended to be remembered and transmitted orally.

A long mythical poem about creation ends thus:

‘Let these verses be held in remembrance and let the elder teach them;

let the wise one and the scholar discuss them;

let the father repeat them to his sons;

let the ears of (even) the herdsman be opened to them.’ - The concluding lines of a creation poem emphasize the importance of passing down the verses through oral tradition, involving elders teaching, scholars discussing, fathers repeating to their sons, and even herdsman listening attentively.

VII. The Uses of Writing

The excerpt from the Sumerian epic poem about Enmerkar sheds light on the connection between city life, trade, and writing in Mesopotamia.

Sumerian epic poem about Enmerkar

- Enmerkar, an early ruler of Uruk, is credited with organizing the first trade of Sumer. He desired lapis lazuli and precious metals from the distant land of Aratta for the beautification of a city temple.

- Enmerkar sends a messenger to Aratta to obtain these goods. The journey is arduous, crossing multiple mountain ranges and encountering various challenges.

- The messenger faces difficulties in convincing the chief of Aratta to part with the desired items, leading to repeated journeys back and forth between Uruk and Aratta.

- Eventually, Enmerkar decides to write down his messages on a clay tablet because the messenger becomes confused and mixes up the spoken words.

- When the ruler of Aratta receives the written tablet, he examines it carefully, emphasizing the significance of the written words.

- While the events of the poem may not be historically accurate, it highlights the understanding that kingship played a crucial role in organizing trade and writing in Mesopotamia.

- The poem also suggests that writing served as a means of storing information, sending messages over long distances, and was regarded as a symbol of the advanced urban culture of Mesopotamia.

The epic poem underscores the interplay between city life, trade, and the advent of writing, portraying the significance of kingship in facilitating trade and the use of written records to overcome the limitations of oral communication.

VIII. Urbanisation in Mesopotamia: Temples and Kings

The notes below describe the development of cities in southern Mesopotamia and the role of temples in the urbanization process. They functions ranged from religious centres to economic and administrative institutions.

- Settlements began to emerge in southern Mesopotamia around 5000 BCE, and some of these settlements evolved into cities.

- Cities were of various types: those that developed around temples and those that became centres of trade.

- Temples, constructed initially as small shrines, gradually grew larger and more complex, with multiple rooms and open courtyards. The outer walls of temples had distinct architectural features.

- Temples served as residences for gods and were the focus of worship. People brought offerings such as grain, curd, and fish to the gods.

- Over time, temples expanded their activities beyond religious functions and became key institutions in urban life. They played a role in processing agricultural produce and became organizers of production, employers of merchants, and keepers of written records.

- Agriculture faced natural hazards such as floods and changes in the course of rivers, leading to periodic relocations of villages.

- Conflicts over land and water resources were common, and successful war leaders could increase their influence and wealth through plunder and distribution of loot.

- Victorious chiefs began offering valuable booty to gods, beautifying temples, and organizing the distribution of temple wealth. This elevated the status and authority of the king.

- Settlement patterns shifted as leaders encouraged villagers to settle near them for rapid mobilization of armies and safety in proximity.

- Uruk, one of the earliest temple towns, witnessed a major population shift around 3000 BCE and expanded significantly. It had defensive walls and ongoing construction activities.

- War captives and local people were compelled to work for the temple or ruler. Compulsory labour involved tasks such as fetching stones, making bricks, or fetching suitable materials from distant lands.

- Technical advances occurred during this period, including the use of bronze tools, construction of brick columns, colourful mosaic creations using clay cones, sculpture in imported stone, and the adoption of the potter’s wheel for mass production.

IX. Life in the City

The notes below discuss the social dynamics and living conditions of ordinary people in Mesopotamia, focusing on aspects such as family structure, marriage customs, and everyday life in the city of Ur. It also shows contrast between the ruling elite and the ordinary people.

- Ruling Elite: A small section of society emerged as a ruling elite with a significant share of wealth. This fact is evident from the enormous riches buried with some kings and queens at Ur, including jewellery, gold vessels, musical instruments inlaid with precious stones, and ceremonial daggers.

- Family Structure: The nuclear family was the norm in Mesopotamian society, and a married son and his family often lived with his parents. The father was the head of the family. Marriages involved declarations of willingness, consent from the bride’s parents, and the exchange of gifts between both families.

- Inheritance: Sons inherited the father’s house, herds, fields, and other property, while daughters received their share of the inheritance from their father at the time of marriage.

- Ordinary Life in Ur: The city of Ur, one of the earliest excavated cities, had narrow winding streets, indicating limited accessibility for wheeled carts. Donkeys likely carried grain and firewood to the houses. The absence of town planning is evident from the irregular shapes of house plots and streets.

- House Structures: In Ur, houses had clay pipes and drains in their inner courtyards to channel rainwater. The lack of paved streets and the practice of sweeping household refuse into the streets led to rising street levels and raised thresholds to prevent mud flow into houses after rains.

- Lighting and Privacy: Houses in Ur received light through doorways opening into courtyards, ensuring privacy for families. Omen tablets recorded superstitions about houses, with certain features believed to bring wealth or luck.

- Burials: Ur had a town cemetery with graves of both royalty and commoners. Some individuals were found buried under the floors of ordinary houses.

X. A Trading Town in a Pastoral Zone

These notes emphasize the rise and prosperity of the royal capital of Mari after 2000 BCE, focusing on its strategic location on the Euphrates and highlighting its role as a thriving urban centre and a hub for trade and cultural exchange.

- Mari is located further upstream on the Euphrates, away from the highly productive southern plain of Mesopotamia.

- The region around Mari was characterized by a combination of agriculture and animal rearing. While some communities practiced both farming and herding, most of the territory was used for pastoralism, particularly sheep and goat herding.

- Herders and farmers had a symbiotic relationship, as they exchanged young animals, dairy products, and meat for grain and metal tools. The manure from the herded flocks was also valuable to farmers.

- However, conflicts could arise between herders and settled agricultural communities. Herders might damage crops by allowing their flocks to graze on cultivated fields, while herding groups could raid agricultural villages and seize stored goods. Settled communities, in turn, might deny herders access to water resources along certain paths.

- Throughout Mesopotamian history, nomadic communities from the western desert migrated into the agricultural heartland. Some of these groups settled down and gained enough power to establish their own rule, including the Akkadians, Amorites, Assyrians, and Aramaeans.

- The kings of Mari were Amorites, who wore different clothing from the original inhabitants. They respected both the Mesopotamian gods and also built a temple for Dagan, the god of the steppe.

- Mari prospered as an urban center due to its strategic position for trade. It served as a crucial trading hub between the south and the mineral-rich uplands of Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon. Goods such as wood, copper, tin, oil, and wine were transported by boats along the Euphrates.

- Mari levied charges on trade goods passing through the city, inspecting cargo and collecting fees. Trade commodities included grinding stones, wood, wine jars, and oil jars. Copper from the island of Cyprus (known as Alashiya) and tin were especially important for the production of bronze tools and weapons.

- Despite not being militarily strong, Mari was exceptionally prosperous due to its advantageous trade position and the wealth generated through trade and commerce.

XI. Cities in Mesopotamian Culture

These notes emphasize the value that Mesopotamians placed on city life and the pride they had in their cities. The city of Uruk, in particular, symbolizes the pinnacle of Mesopotamian civilization and stands as a reminder of their urban pride. It particularly highlights this sentiment through the example of the Gilgamesh Epic and the city of Uruk.

- City Life Valued: Mesopotamians cherished city life, where people from diverse communities and cultures coexisted. Cities were centers of social, economic, and cultural activities and represented the pinnacle of human civilization.

- The Gilgamesh Epic: The Epic of Gilgamesh is an ancient Mesopotamian literary masterpiece, written on twelve tablets. Gilgamesh, the protagonist, ruled the city of Uruk, succeeding Enmerkar.

- Gilgamesh’s Quest for Immortality: When Gilgamesh’s heroic friend died, he became determined to find the secret of immortality. He embarked on a journey across the waters that surrounded the world in search of eternal life.

- The Failure and Return: Despite his heroic efforts, Gilgamesh failed to obtain immortality. Disheartened, he returned to his city, Uruk.

- The Pride in the City: Gilgamesh finds consolation and pride in the city he ruled. He walks along the city wall, admiring the foundations made of fired bricks that he had constructed. The city represents the enduring legacy of his people and their achievements.

- Contrast with Tribal Heroes: The passage highlights a contrast between Gilgamesh and tribal heroes. While tribal heroes might boast about their lineage and how their sons will carry on their legacy, Gilgamesh finds solace in the city he helped build, recognizing that his people’s collective accomplishments will outlive him.

XII. The Legacy of Writing

These notes emphasize the significant contributions of Mesopotamia to the world’s scholarly traditions. Mesopotamia’s scholarly tradition, rooted in writing, education, and practical applications of mathematics, played a crucial role in shaping the foundations of science and intellectual development that continue to influence the world today.

- Scholarly Tradition: Mesopotamia’s greatest legacy is its scholarly tradition, which involved the development of written texts that could be passed down through generations of scholars. This allowed for the accumulation of knowledge and the ability to build upon previous work.

- Mathematical Tables: Tablets dating back to around 1800 BCE have been discovered, containing multiplication and division tables, square- and square-root tables, and tables of compound interest. These tables demonstrate the Mesopotamians’ understanding of advanced mathematical concepts.

- Calculation of Square Root: An example is given of a square root calculation, where the tablet provides an approximation of the square root of 2. The result, although slightly different from the correct answer, shows the Mesopotamians’ sophisticated numerical abilities.

- Problem Solving: Students in Mesopotamian schools were presented with practical problems to solve, such as determining the volume of water in a field based on its area and depth. This demonstrates the application of mathematical concepts to real-world scenarios.

- Time Reckoning: Mesopotamians played a crucial role in dividing time into units that we still use today. They divided the year into 12 months based on the lunar cycle, the month into four weeks, the day into 24 hours, and the hour into 60 minutes. These divisions were later adopted by various civilizations and transmitted to different parts of the world.

- Observational Records: Mesopotamians kept detailed records of celestial events such as solar and lunar eclipses, as well as the positions of stars and constellations in the night sky. These records were noted by year, month, and day, indicating their understanding and observation of astronomical phenomena.

- Importance of Writing and Education: The achievements of Mesopotamian scholars would not have been possible without the development of writing and the establishment of urban schools. Students in these schools read and copied earlier written tablets, and some were trained to become intellectuals who could advance knowledge in various fields.

- Preservation of Texts and Traditions: The passage briefly mentions early attempts to locate and preserve texts and traditions from the past, highlighting the Mesopotamians’ recognition of the value of historical records and their efforts to safeguard and pass on knowledge.